This is a (short) series on transcendence, exploring the ways we seek, and find, transcendence from our objective, observed reality. This idea was inspired by my own personal transcendent experiences, but also baked into my DNA—I was raised Catholic, Appalachian, and Lebanese. The first essay is about transcendence through spirit, by which I mean, communicating and/or seeing spirit(s), right here on earth.

***

The story goes, when my dad was six, he awoke one day with both hands covered in warts. His mother, a Scots-Irish woman from the depths of Boone County, West Virginia (think: hill is heel; kill is keel) didn’t haul him to a doctor. Instead, she traipsed him through the woods, to see what some might call a folk healer, or medicine woman. Local Appalachian lore describes these women as essential and historical parts of community, employed in earnest to heal by prayer, root, herb, or dirt1; many of them were just somebody’s grandmother. For decades they filled a niche between witch, healer, naturopathic doctor, and soothsayer. It didn’t matter that the region thrummed in Christian vein, or that theirs was wisdom gleaned mostly from indigenous practices, both Native American and Irish (though there were certainly Christian elements, too)2—most everyone, regardless of creed, believed in this type of medicine, sought it out at one time or another because it delivered.

This particular woman, in this particular wooded nook of Boone County, examined my father’s hands and took twine, tying a knot around each wart. She removed the knots for keep, supposedly to bury in the dirt later. She spoke a promise, that in a day or two, the warts would be diminished if not gone. And according to my father’s many retellings, he indeed awoke a few mornings later, hands clear.

I found near identical versions of this story across the internet—other young and warted children, other women in the woods tying knots of string, all over Appalachia, from Georgia over to Arkansas.3 This continuity only served as proof that this practice was spiritual but also methodical, its tenets spanning wide likely by oral tradition alone.

Throughout their lives, my father and grandmother shared many other supernatural visions which they both vehemently swore up and down were true. Every tale was accounted for by the other. They watched from the kitchen window as a roaming light they determined to be a UFO shifted back and forth, up and down in linear trail—movements they swore were unintelligible to the technology of the time; the light was swallowed suddenly by black sky. Or when they both struck glimpse of the one we Appalachians call Mothman, spotted on an unlit back road of a late night’s drive.

All visions aside, my father would likely be considered an analytical, rational man. He liked numbers, could complete complex mathematical equations in his head without assistance from calculator or paper. He was interested in technology and politics. He informed me quite early that Twitter would transform our media landscape; I informed him people would never be that interested in the mundane, random thoughts of others. He debated and challenged my more emotional inclinations until I grew hot in the cheeks with frustration. I realized only later that he was confronting my convictions to forge them, not change them. I was young and liberal, in constant attempt to project my principles to others. You can’t cure the world, Elizabeth, he’d say in attempt to ground my expectations. And yet, concurrently, he retained that parcel of himself that believed in UFOs and a Mothman, the part that believed in a sight beyond reason.

***

Besides being my father’s daughter, I blame, in part, my Catholic upbringing for any bend toward belief in the supernatural. The Bible itself is full of mortals enacting magic. Jesus himself was proved divine by supernatural gesture—healing the sick, walking on water, multiplying fish and converting water to wine. He might even be called, according to a modern framework, a psychic medium—psychic because he demonstrated omniscience through predictions came true, and medium because he served as a portal between God and man, channeling his father’s lessons to others. Jesus held divinity in his nature and was thus able to extend his human faculties to communicate beyond the physical plane. But mere mortals, too—think, Moses—channeled the word of God in creation, the received messages comprising the first chapters of the Old Testament. And still, if someone earthly claims to meet the divine in supernatural terms? They can even be ordained a saint.

In the fifth grade of my Catholic grade school, we were tasked with choosing a saint to research and present to the class. Due to my young proclivity for ghosts and French culture, I chose the French Saint Bernadette Soubirous, who, at 14-years-old, witnessed apparitions of a young lady she claimed was the Virgin Mother.4

Bernadette was out gathering firewood in the woods with her sisters when the young Virgin first appeared to her near a grotto; she returned to the grotto again and again, and the visions persisted, a total of 18 times over a fortnight. As word spread and crowds formed to bear witness to (or debunk) this miracle, others remained blind to an apparition’s presence. They only described Bernadette entering what they called a state of “ecstasy.”5

Born to a fairly prosperous family just outside Lourdes, France in 1844, Bernadette’s father was once a successful miller, meaning he worked in water mills until industrialization took hold and plunged the family into poverty. They were forced to live in a cramped room of an unused prison, where they endured periods of famine and disease. Bernadette herself remained illiterate all her life, and yet, Mary appeared to her vision alone.

Bernadette’s claims were officially investigated by the church. It was a Monsignor Laurence who interviewed her and recounted being struck by her clarity of conviction. He wrote, “ …and to all the questions put to her, without hesitation, she gave clear, precise response, impressed with a strong conviction.”6

After the visions, Bernadette rejected any monetary compensation, as well as an ensuing fame that surrounded her sensational story. She instead chose to hole up in a monastery to tend to the sick, and lived out the rest of her life in privacy and piety. She remained, by all accounts, uneducated, impoverished, and sickly, though she did confidently lay claim to the clarity of her own vision and her deep, unmovable faith—which one today might call clairvoyance.

***

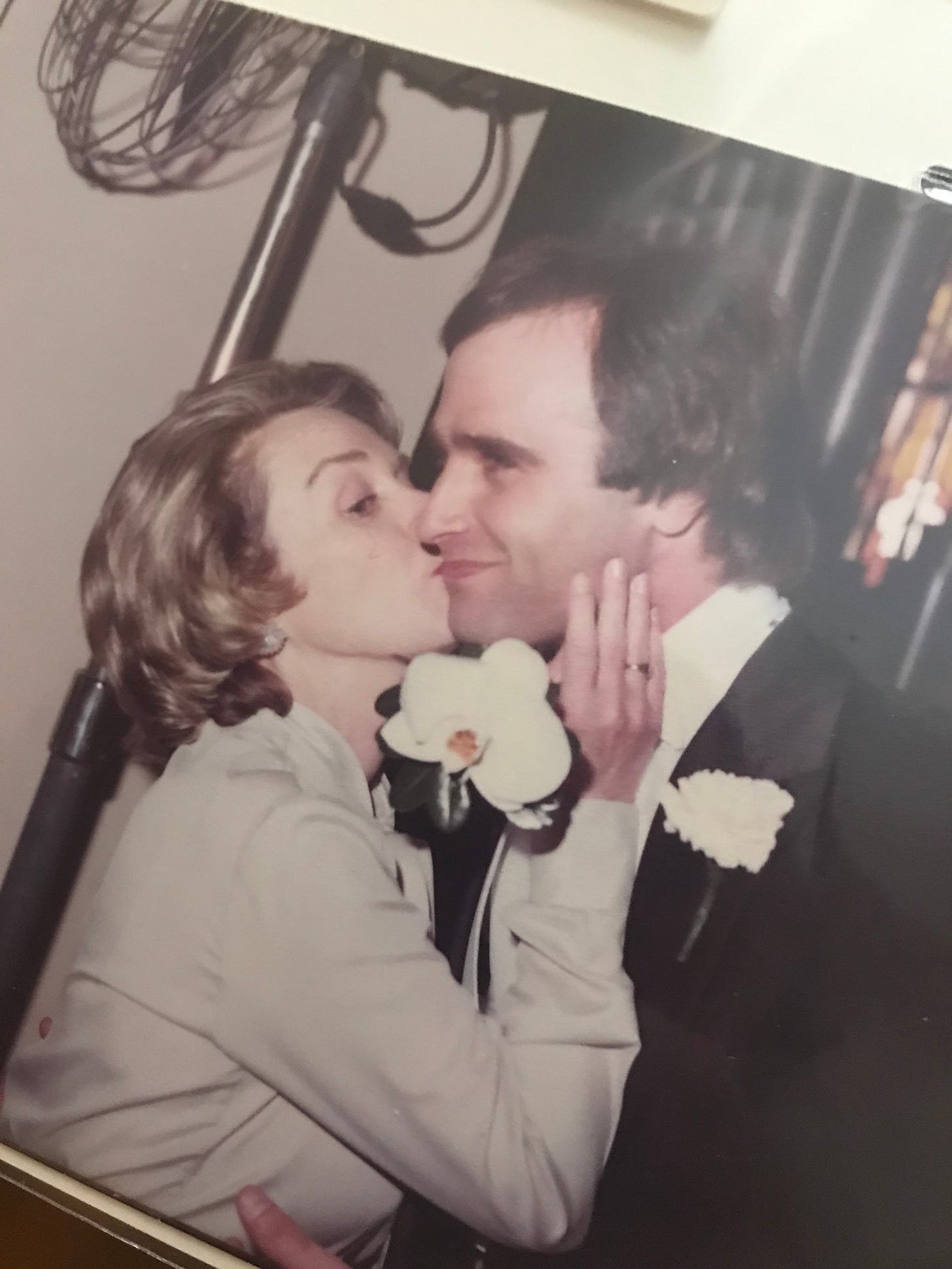

My father died suddenly when his aortic artery burst; he was 59 and I was 22. I happened to be home visiting for the Easter holiday, present to collect the visions of his death. My brain rendered what I witnessed into fragments, fixing themselves into memory like intrusive, flashing pixels. They still tick up sporadically, overlaying themselves upon unrelated matter in subliminal reminder, fifteen years on.

Within the obscurity of grief, I searched for shape and specificity. I longed for the abstractness of death to be made concrete, as it can unmoor even the deepest of beliefs; faith in the unseen was suddenly a thing too sheer. I needed someone with a power akin to the Boone County medicine woman, someone with the type of supernatural vision my father and grandmother believed in, might have even possessed. So I made an appointment with a psychic.

I arrived at her apartment free of skepticism, not only because grief dissolves barriers between reality and delusion, but also this was a time before the internet decreed every memory and life event public and archived; I had a sense I could suss out any nefarious or dishonest intent. She was immediately taken aback by what she perceived to be the strength of my father’s presence. “Did he just pass?” she inquired almost as soon as she opened the door. We took place at a small table shoved into a midtown New York City kitchen corner. She closed her eyes in meditation though they fluttered persistently half-ajar.

She spoke clearly and in streams of consciousness. It was in the way she recounted exactly how my father died, not physically (though she did point in the direction of an aorta) but spiritually, existentially. Through her Long Island lilt, my father described death in his most defined, analytical terms: what he felt, what he saw, the way he clung to body by crouching his spirit (the psychic covered her head with her hands in a crouch). He knew if he looked up, he’d be gone. He waited to leave body, he said, until I arrived at the hospital. And he spoke of his after-life greetings, too. He shook his father’s hand when he arrived. Isn’t that funny? He’s chuckling. And that is exactly how my grandfather would greet my dead father’s spirit, after all those years, I thought—with a handshake.

For over an hour, he-through-she described in meticulous detail not just the eve of his death, but the haze of days after: my mom placing my father’s reading glasses on her nightstand in memory, leaving the bathroom light on at night for comfort, both which she didn’t do before; my sister, too, encasing photographs in glass, which I later found out she was indeed doing at the exact moment of my appointment, framing and decorating photos of my father. The psychic described my father’s earthly existence, too—the wood panels of his office, his ever-black hair and tanned skin, his approximate height, the shape of his jaw. Still, my father continued to impress upon her to explain to me what it’s like to die; though this psychic supposedly talked to the dead often, she never before heard such deep analysis of death’s procedurals before. And this, too, was just like my father. He would die and circle back to provide the analysis, Elizabeth! This is what happens. It’s fine.

Of course, the afternoon I spent communicating with my dead father might read vaguely suspicious to another’s skepticism, someone who isn’t a grieving daughter searching the air for a sign. Yet before that day, I spoke into the ether, asking my father, again and again, sometimes out loud, mostly in my head, What happened to you? Where did you go?

And perhaps, one could believe, he answered me.

***

The metaphysical often refers to that which cannot be directly observed or empirically studied. Psychic ability falls in this realm. There are various transcendent capabilities a psychic might claim to possess depending on the faculties she claims to extend. There is the gift of clairvoyance, or sight beyond the limit of space and time; a clairvoyant is often able to predict by vision a future or past. And then there is clairaudience, or the ability to hear beyond our earthly acoustic plane; in this case, predictions are usually received aurally, in language. And there is mediumship, or the act of channeling, which exists within clairvoyance and clairaudience, though not necessarily. Channeling extends the faculties to the foot of the dead. The psychic I visited claimed to possess all three. She even told me I’d be a writer.

Clairsentience, or the extension of feeling beyond, decrees feeling a sensorial faculty like sight and hearing. It is also called intuition, or the gut feeling we all experience from time to time, likely the most common of all psychic abilities. Though feelings can be deduced as information gathered by the rational mind—one produces feelings about another, good or bad, through social inference, for example—clairsentience is believed to be a feeling received from transcendent frequency, a gathering of information by feeling, not from observation but by otherworldly messaging.

Scientists and philosophers have long attempted to quantify the metaphysical. Is perception reality? And what is perception? What is reality? Kant believed metaphysical matter would always remain unknowable, though not necessarily untrue; he retained room for belief. Plato believed everything, including concepts, objects, and even people contained an overarching, higher essence, or form. (Also known as The Platonic Ideal.) He argued metaphysical reality as a rational truth. Descartes would be entirely skeptical of my psychic experience, because he believed the senses often deceive us, can’t be entirely trusted. And Sartre believed consciousness was indeed transcendent, constantly aware of a world beyond itself, though he grounded this transcendence in the earthly plane, not some supernatural realm we might access.7

Modern scientists have taken up matters of the metaphysical in legitimate study. Dr. Helene Wahbeh conducts research she believes lends proof to the human capacity for transcendence. She mostly studies, and argues that science proves, the human ability for psychic communication and mediumship. She claims to publish quantifiable data that proves sensorial faculties can be extended like antennae, can access information beyond observation alone. She even wrote a book called The Science of Channeling—two fields traditionally pitted as diametrically opposed to each other.8

The most convincing proof that consciousness can be expanded like elastic through the body’s senses, lies in the realm of communication with and amongst animals. In the second episode of popular podcast “The Telepathy Tapes”, hosted by Ky Dickens—which, as the name suggests, explores matters of psychic ability and telepathy (though mostly in regards to autistic children)—a woman named Ditte Young was interviewed. She claims to communicate by trade with animals through telepathy, and to have assisted champion equestrians and their horses struggling with unresolved issues like anxiety, medical problems, or even an inability to jump. Through Young’s telepathy, she even claims a horse diagnosed their teenage rider with arthritis, the horse sensing, and thus acting to protect, the young girl’s warm and inflamed knees. Of course, Young led with all anecdotal accounts, though were convincing. And the podcast itself is criticized often for its dependence on anecdote, its’ lack of scientific rigor.

I myself have an extraordinarily intuitive bird dog, and I take notice of how she communicates subtly with both humans and other animals. Her awareness is spiked not just through body language and scent (a dog’s most heightened faculty) but also by an uncanny predictive energy. She acts morose minutes before I give indication I am planning to leave; she begins to to pace right before I pull out a suitcase to pack for travel. Sometimes, she gets up from a dead sleep to look out the window, right before my husband crosses the street to return home.

Is there a science to it? The true beauty of accessing realms outside our own, or even holding it as possibility, is really just a matter of belief. And belief can be a hopeful human endeavor, faith in the unknown a conviction that lends strength (though both can prove dangerous, too; more on that, later). Through religious or spiritual devotion, or even paranormal intrigue—and even if part of an organized group—faith requires trust in the self, a sensitivity and discernment in one’s own faculties. And though I myself have grown more skeptical in age, I find belief in transcendence in the form of spirit or the supernatural to be a startling act of commitment to one’s own wits.

***

While someone like a psychic or medicine woman is transcending reality through expansion, by an opening of the senses, she must first go within; it really begins in contraction. Meditation is usually the way in to consciousness, toward the deep, internal space of awareness where a mind cracks open to the metaphysical.

But meditation isn’t always just sitting silent with eyes closed. An inner meditative state can be accessed by external stimuli. The most available manifestation of channeling through body is dance, a transcendence usually reached with eyes wide open; and the most accessible expression of clairaudience is music, both in its creation and one’s experience of it. Writing, too, is a channeling awake; the writer goes within to meet others, real or imagined, and uses every faculty to hear, envision, and emote their story.

We are all tuning in to tune out. As Wordsworth wrote in the poem, Expostulation and Reply,

The eye — it cannot choose but see;

We cannot bid the ear be still;

Our bodies feel, where'er they be,

Against or with our will.

Parts II and III of How To Transcend a Life, incoming.

I found this article well after I wrote this line; and this article includes a line almost identical to the one I wrote—only more anecdotal proof that we are all indeed drawing from the same, higher source. Still, to avoid a plagiarism charge, I am citing this article, and this line in particular. “Regardless of naming conventions, Southern Appalachian folk healing modalities—using plants, prayers, herbs, and dirt to heal illnesses, ward off evil, and protect the home—reflect the vibrant cross-section of people who initially inhabited the area from West Virginia down into Mississippi.”

All this knowledge learned in philosophy class at Fordham University, over 15 years ago. Thus, my understanding of philosophy might be shaky—if my analysis is wrong, please advise!—but I was always enthralled by the subject nonetheless. I wish I remembered the professors names, but I don’t.

https://noetic.org/profile/helane-wahbeh/