Five Wisdoms for a New Year

My introduction to a new series I will publish in five parts, called "Five Wisdoms;" and the first wisdom, "Fame Will Only Take You Down!" Via Glenn O'Brien, Jim Harrison, and Shoshana Zuboff.

INTRODUCTION TO “THE FIVE WISDOMS.”

I turned 38 in October (for your notes, it was the 27th, me and Frank Ocean) and I have since been reflecting on such precipices of age. When you are hemming close to another decade—in my case, the forties—everyone begins to existentially round up, which is a good example of how inclined we are to disregard the extant. According to widely accepted semantics, we do (somewhat suddenly) cease growing—at 30, 35, maybe?—and commence aging. I can’t pinpoint when it turned for certain, but I was referred to as “young” until only recently; strange, since 38 feels verifiably young but might factually be considered middle aged.

There could be a gendered anxiety to aging. As Susan Sontag noted in “The Double Standard of Aging,”

The discomfort a woman feels each time she tells her age is quite independent of the anxious awareness of human mortality that everyone has, from time to time. There is a normal sense in which nobody, men and women alike, relishes growing older…It is particularly women who experience growing older (everything that comes before one is actually old) with such distaste and even shame.1

Though I know and feel deeply the weight of gnawing invisibility age can thrust upon (mostly) women—usually in its visual insignia, a slacking face or graying hair—I have long admired older women. I feel a certain contention with the tendency we provide women to panic about aging. Growing up, my mother’s friends, especially those in their 40s, fascinated me. I loved the idea of an older life, one laden with a sophistication and intrigue that can only derive from self-assured motive, from knowing thyself. These older women moved with a freedom youth could never possess, which made me ache to age. I was correct, in a sense; youth is often associated with freedom but is full of anxiety, the uncertainty of lacked experience. It is age that releases us from such constriction, the tedious self-awareness that inhibits most youth.

Aging is also a careening toward death, a correlation I didn’t give proper credence to when young. (Though, given an intense anxiety disorder, I did think about immediate death often, likely more than most). It’s amazing how acutely we remain unconscious of time until ours is nearly depleted, until it turns impossible to ignore. When time arrives (or diminishes), a despairing fear inevitably kicks in, brought on by either illness or just a shock of number. It is really amazing how little we think about death at all.

I have been contemplating age and death, obviously, but more so wisdom’s relation to time. It would be prudent to refer to the ever-passing years as experience, since all one can hope for is that memory survives as the body degrades; perhaps in the end there is only what happened and our perception of it. Remember Joy Williams:

As regards to life it is much the best to think that the experiences we have are necessary for us. It is by means of experience that we develop and not through our imagination. Imagination is nothing. Explanation is nothing. One can only experience and somehow describe–with, in Camus’s phrase, lucid indifference. At the same time, experience is fundamentally illusory. When one is experiencing emotional pain or grief, one feels that everything that happens in life is unreal. And this is a right understanding of life.2

I’m surely not as vacuous as I was in my twenties or early thirties, and wouldn’t wish return to even the uncertainty of 35. How stupid I was! How stupid I will become, what a difference a year will make. Still, I wonder if I have accrued anything I might call wisdom. What is wisdom anyway? Is it simply an accumulation of knowledge or something deeper, more existential? In Plato’s Republic, Thrasymachus irritably chides Socrates’ means of acquiring wisdom:

That is Socrates’ wisdom for you: he himself isn’t willing to teach but goes around learning from others and isn’t even grateful to them.

To which Socrates replies,

When you say I learn from others, you are right, Thrasymachus; but when you say I do not give thanks, you are wrong. I give as much as I can. But I can give only praise, since I have no money. And just how enthusiastically I give it, when someone seems to me to speak well, you will know as soon as you have answered, since I think you will speak well.3

Of course, we have already deduced that wisdom is likely greater than any assemblage of information alone, remains intricately entwined with one’s experiences in life. But reading, though not a sole source, persists as an essential form of wisdom if only because it has a widening potential to force us into confrontation with thoughts and realities most unlike our own.

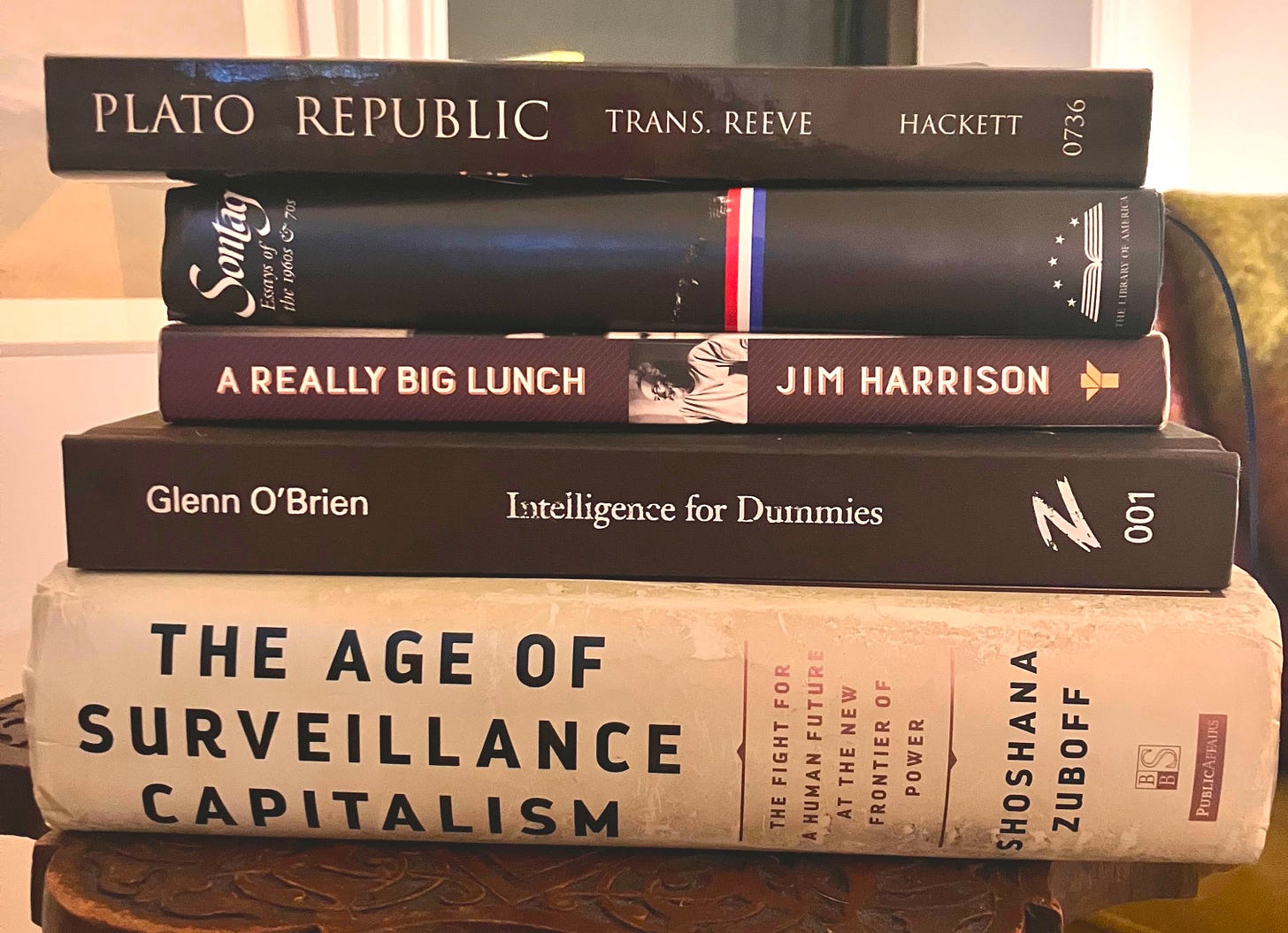

In honor of birthdays and a new year and diminishing time, this will be a short series of five wisdoms gleaned from lines, excerpts, and sentiments of some of my favorite writers. I will call it, aptly, Five Wisdoms. I hope to express my gratitude, in praise, for the writing that has provided me a sort of intellectual wisdom. For brevity, I narrowed it down to a few: Glenn O’Brien, Jim Harrison, Joy Williams, Susan Sontag, Rita Dove, Shoshana Zuboff, Lauren Oyler, and Tom Robbins.

This will be writing heavy on quotations. I indeed have my own point of view, but believe it important to likewise lend credit to those who helped shape it. As a late bloomer and a self-taught writer of criticism (barring two years of journalism study, if that counts), I am perhaps greener and less jaded than other writers in my enthusiasm for discovery by reading. There are endless hot takes available on this platform—this is not that, but rather an observance of such learning, a library as a school, in perpetuum.

***

WISDOM 1:

Fame Will Only Take You Down! Or, “To be known of is to never be known.” (Via the writing of Glenn O’Brien, Jim Harrison, and Shoshana Zuboff.)

Celebrity as we once knew it is dead, though a few previously blinding stars clutch on—giants like Taylor Swift and Beyonce, perhaps a Leonardo and a Denzel. This sort of stardom fractured into parcels of shifting luminosity, and in its stead we have been willed fame—celebrity’s lesser and more splintered sister. There is now a myriad of ways to become famous, a state of being achieved almost too easily. Modern fame is made up mostly of the internet kind—which is often relayed as a kind of democratization though I think it perverse; modern stars are almost so abundant they have been inadvertently dimmed. There does remain a hierarchy, with renown via television and cinema still being most revered and respected. But will Timothy Chalamet ever be sought quite like Brad Pitt? Will Sabrina Carpenter ever loom wide as Taylor Swift? It seems there is no heir to Michael Jackson’s infamy waiting in the wing.

Writer Glenn O’Brien really grasped celebrity, in culture and psyche. He was a downtown New York fixture of mid-century, a prolific writer, editor, art critic, and even, briefly, television host; but much of his notoriety derived from being part of Andy Warhol’s Factory—a cultural milieu rife with celebrity, one I surmise will remain more remarkable than any contemporary movement. Suffice to say, O’Brien knew celebrity intimately.

He served as Warhol’s primary recorder of scene—working as an early (and many times over) editor for iconic (and Warhol-founded) Interview magazine, as well as publications like Rolling Stone. In “I Remember the Factory,”4 the famous roam in and out of the Factory more like civilians pining for a fame Warhol presided over, rather than as recognized icons. (Which simultaneously paints them as far more interesting than any one biopic could.)

There was Fran Lebowitz (who recently resurged as a modern sensation) being annoying:

I remember Andy asking me why I didn’t get rid of Fran Lebowitz and asking me if she was really funny.

And David Bowie:

I remember when David Bowie came to visit Andy saying, ”Should we let him in?”

Also:

I remember David Bowie coming to the Factory to do a mime act for Andy and sing “Andy Warhol.” Paul wanted to throw him out, but I told Andy he was famous in England. After the song Andy didn’t know whether to be insulted or not.

And there was Bob Dylan being overly concerned with image:

I remember Bob Dylan’s bodyguards grabbing Andy’s film at Mick Jagger’s birthday party because there was a joint on the table.

In Intelligence for Dummies, the posthumous collection of O’Brien’s life’s work, one senses a convincing irreverence, a writing unconcerned with any overly sensitive inclination; he waded into darkness not only to illuminate it but to make fun of its banality. In an essay titled “Sympathy for the Taliban,”5 he found a sliver of poignancy in the Taliban’s brute destruction of ancient Buddhist monuments (also designated UNESCO World Heritage Sites):

I think that in a very extreme way they are making a point that is well taken. It certainly would have been more appropriate if they had trained their artillery on, say, Disneyworld, the headquarters of InStyle magazine, the Jerry Springer show, Julian Schnabel’s studio, or every copy of the film Titanic, but the rural zealots struck the only targets they had in range, the big old stone Buddhas.

Though O’Brien was edging toward the absurd, he was exposing a patent truth—the Taliban’s much-maligned radicalism only informs our own.

Western culture is idolatrous in the extreme. We worship images: famous faces, logos, trademarks, computer retouched photos of surgically enhanced mammaries, and high-end consumer goods. And this is bad.

(If you were on the verge of being offended, don’t worry; he began the piece with a statement: “Probably, if given the opportunity, I would beat Osama Bin Laden to death with the Manhattan Business-to-Business Yellow Pages without giving it a second thought. I don’t like all this fundamentalist poop.”)

In “How to Avoid Fame,” (aptly published in Bergdorf Goodman Magazine), O’Brien mused, “Fame makes a few things better. But it makes most things far, far worse.” Instead, he advised, “Find a nice comfy niche in the lower ranks of notoriety and stay there. I have.”6

Of course, he wrote that in 2007 before fame separated from celebrity and aerated into an illness that can infect any of us, even those of us devoid of talent, even if by accident. One’s personal level of fame, it seems, is almost terrifyingly out of one’s control. Of course, many of us touch every surface and lick our fingers in hopes of catching it. But there now exists great potential to become famous (or infamous) inadvertently, if caught by an insidious camera doing something funny or dubious, like having a bad day or speaking out of turn.

One might wonder if the kind of niche fame O’Brien advised—which I would identify as respect for one’s craft, or the noble recognition of one’s talent—is possible now. With ubiquitous visibility normalized and sanctity of privacy forgone, fame has shape-shifted into something near mundane. I myself experience difficulty assigning certain life events value unless others bear witness to it, a chilling shift in brain chemistry.

O’Brien seemed to play fame right. He remains widely revered, ever cool, but not so known that his work, which has a real latency to offend, might get him “canceled” on Twitter, a platform he did use before his death—though we seem to have left behind the dull collective urge to virtually eradicate someone on the basis of offense. Anyways, as mentioned, O’Brien is dead, so he doesn’t have to worry about things like that.

There is (hopefully) an epiphany in maturation: that the more visible one becomes, the less known. “To be known of is to never be known,” is a line from a poem I wrote (“Barriers”) and a maxim I gleaned from experience. What gives me authority? Besides the fact that growing up I was obsessed with celebrities? In my early twenties, I struck semi-successful as a “blogger” (a moniker I never truly embraced) by creating a website (blog) where I wrote through a chosen niche: the ritual of coffee. Few people understood the project at all—it wasn’t really about the coffee!—which was only an echo of both my naivety and my admittedly young, mediocre writing. Much of the engagement became largely pictorial, as everyone seemed focused on the images—photographs of what I ate, places I traveled to, things I wore. I soon became an empty avatar.

Publications requested use of my photography; a producer for the Travel Channel hoped to test my idea as a TV show; fairly famous advertisers inquired sponsorship. I indeed considered the opportunities, but couldn’t shake the concern that I no longer worked in the development of craft or the dissemination of novel information, but instead became readdressed as a hack exploiting daily life for (very little) gain. It happened slyly, like a sleepwalking. I eventually abandoned the blog for a much more boring pursuit: content writing for others. I only look back on that period of my career as harboring a most deadening and uncreative quality.

Of course, becoming famous for the intricacies of one’s life, which is what most of us do online, presupposes that what we do is inherently interesting and/or important—a delusion we are all afflicted with, especially writers. In “Everyday Life: The Question of Zen,” Jim Harrison noted, “To know the self, of course, is hopefully to forget the self.”7

This might sound like an ethical appeal but I promise it’s empirical. Though I could never really claim fame I grazed it close enough, became known enough by strangers online to learn it can never gratify. It does invite unnecessary and uncritical opinion; the positive kind proving mostly futile, the damning kind overwhelmingly mood (and behavior) affecting.

There’s also the reality that the more visible one becomes, the more resented. Via Glenn O’Brien, again instructing us “How to Avoid Fame:”

But above all, most of the people who read about you and are jealous of your beauty, your talent and your good fortune will all be rooting for your utter ruin; your impoverishment, physical debilitation, incarceration and most likely, your painful, ignominious death and utter oblivion to future generations.

I know it would be easy to give in and become a household name, but don’t.

He continues:

Academics are safe. Becoming a poet, novelist, or jazz musician almost ensures a safe degree of anonymity. If you must write, slug it fiction or risk the wrath of Oprah. Be an essayist. No one will know who you are.8

Perhaps most acutely, fame is a stark violation of privacy, a concept that held innate value for millennia though Musk and Zuckerberg are relentless in their pursuit to convince us otherwise. Of course, I’m not suggesting one become a reclusive ghost either, unless one desires such a life. But it is only wise to grow conscious of the system in which we must operate—and maybe even try to break free.

Online structures are built to nudge us toward this natural seeking of fame—through our most basic human need of recognition—with sinister motive: these companies are actively altering behavior by instilling the belief that life cannot glean value unless it is shared with others for maximum online feedback. Coincidentally, such sharing is a gift to the overlords, in its ample and overflowing data. Technology is no neutral tool and it’s not hysterical or luddite to fear it’s incarnations; most modern technology—the internet and social media included—is constructed to infiltrate the most sacred and private elements of a life, to invade home and mind to ultimately procure data and drive consumption. These platforms have convinced us, widely and easily, that our most treasured and private moments must be made supremely visible, that the most weighty moments are not to be experienced but rather composed for witness.

“Ubiquitous connection means that the audience is never far, and this fact brings all the pressures of the hive into the world and the body,”9 writes Shoshana Zuboff, a scholar of technology and capitalism, in her book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism.

It is our task to remember our autonomy and individuality, our right to privacy, to sanctuary.

Inside the hive, it is easy to forget that every exit is an entrance. To exit the hive means to enter that territory beyond, where one finds refuge from the artificially tuned-up social pressure of the others. Exit leaves behind the point of view of the Other-One in favor of entering a space in which one’s gaze can finally settle inward. To exit means to enter the place where a self can be birthed and nurtured. History has a name for that kind of place: sanctuary.10

Of course, there are the superlative humans particularly crafted for fame, even celebrity. These are the movie stars and pop singers gifted with a mix of alien aptitude and a capacity to endure a global gaze. There are also the gifted who made the ultimate sacrifice for celebrity —think Amy Winehouse, Kurt Cobain, or Whitney Houston. Despite the gifts they provided us, we excavated their lives to depletion; we as consumers are partly to blame for their demise. The rest of us are wrought by gravity and egos too easily bruised and thus should probably plant our feet to ground. Some of us must even learn to be fulfilled in the dark, in a space between anonymity and mediocre eminence.

Anyway, I accidentally heeded O’Brien’s advice: I am a poet and I write essays and hardly anyone knows me. That said, one can purchase my book here.

Susan Sontag, “The Double Standard of Aging;” Sontag: Essays of the 1960s and 70s, pages 745-746.

Joy Williams, “Hawk,” published in Granta, 1999.

Plato, Republic, page 14 (338a-338c).

Glenn O’Brien, “I Remember the Factory (After Joe Brainard),” Unpublished 2001; Intelligence for Dummies, page 131.

Glenn O’Brien, “Sympathy for the Taliban: A Modest Proposal for Times Square,” originally published by Arena Homme +, Fall 2001; Intelligence for Dummies, page 170.

Glenn O’Brien, “How to Avoid Fame,” originally published by Bergdorf Goodman Magazine, 2007; Intelligence for Dummies, page 324.

Jim Harrison, “Everyday Life: The Question of Zen;” originally published by Brick, 2001; A Really Big Lunch, page 272.

Glenn O’Brien, “How to Avoid Fame,” originally published by Bergdorf Goodman Magazine, 2007; Intelligence for Dummies, pages 324-326.

Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, page 472.

Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, page 474.