What am I doing here?

A revised mission statement; an evolution; some personal background; a lamentation of the algorithm; a vow and a plea to create; and an introduction to a more creative series; etc.

This is not so much an essay as a reintroduction and repositioning of myself and this project, along with some thoughts about the platform, Notes, what I want to write about, and the new series I shall be launching.

I started this “newsletter” – or page, website, stack, whatever it is to be called – for the same reason as most everyone else: to have a centralized place to publish writing that I couldn’t get publications to look at. I likewise sought space to support a more regular writing practice, though I wasn’t sure what shape or form it would ultimately take.

With Substack comes a supposed built-in reader network, which can provide an opportunity for readers to discover novel (meaning new) writers. But it’s also a bit of illusion, as it’s incredibly difficult for the unknown writer to reach said audience unless they are already famous or worse, engage regularly with the social media aspect of the site, which manifests as the Notes page and is ruled by an omnipotent algorithm.

Does the cream still rise to the top of the matrix? Does writing have value in isolation, or only when experienced by another? I do know it’s unrealistic to expect any writer to not naturally lament when their work is barely read; I know I do. On the other hand, the internet provides too much possibility to color one’s delusion concrete; just because I publish writing on a platform, who should call me a writer? Any accompanying doubt springs from a deeper well than feeble Subscriber count. It’s of a viable concern: who am I writing for and why? And am I even any good?

Alas, an algorithm isn’t some vanishing hand but rather foundational footing. As Shoshana Zuboff wrote in The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, every online platform is riddled with “the problem of two texts.” The first text being all that we create and consume; as Zuboff writes, “we are its authors and readers.” On Substack, this becomes literal. But no platform presents this primary text unmediated. “The first text, full of promise, actually functions as the supply operation for the second text: the shadow text.” The shadow text is the output of information after it has been run through a platform’s coded machinery; this includes data mining, fed by algorithm. The algorithm, then, becomes quite world building: “Despite their claims of objectivity and neutrality,” Zuboff writes, “they are constantly making value-laden, controversial decisions. They help create the world they claim to merely ‘show us.’”

Every online social platform has adopted this architecture, though some more insidiously than others. We can only assume, then, that Substack’s algorithm is no different than the rest—although the informational input may be more literary or philosophical, the end is the same: virality, or what propels the emotional click, brings data to the yard. Everything built online is constructed of the same bone.

Where else might a writer go? Sharing writing on Instagram is demoralizing, as the audience seems almost repelled by the literary. Though I do embarrassingly like/hate Instagram since I tend to gravitate toward visuals. One can sometimes scroll upon a more interesting account, though every session seems to end by a lowbrow meme, a purchasing of a new concealer, yet another dog coat supplement.

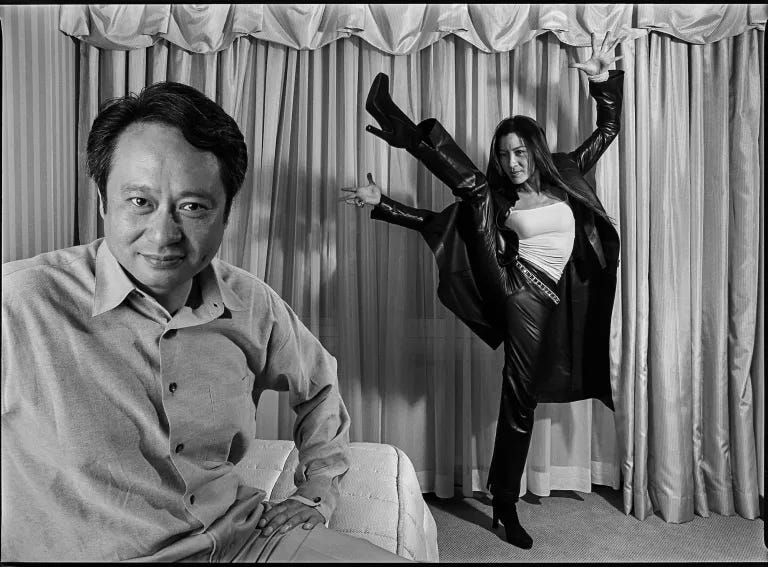

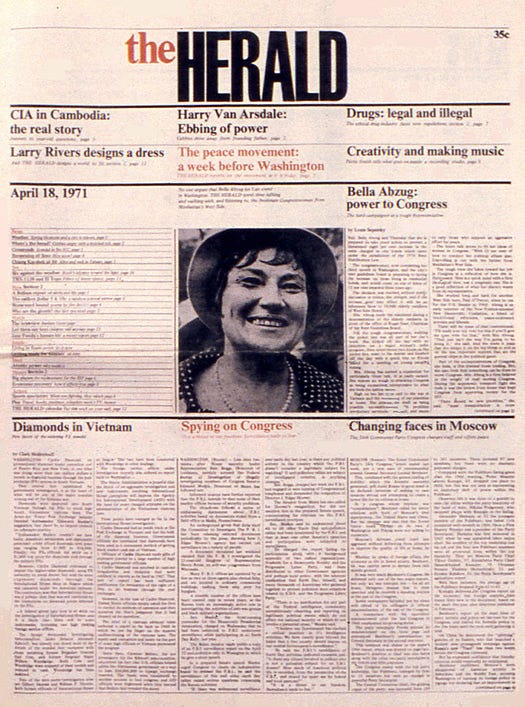

Aesthetics are a vital and often forgotten part of the dissemination of writing. Think of how pleasurable it must have been to pick up a copy of The Herald, designed by Massimo Vignelli! Or to seek out a new James Hamilton photograph in The Village Voice. Of course, the writing has to be good. But the visual and the written are two hands of one body.

No online platform could ever recreate the amount of presence arrived from gleaning information by newspapers and magazines alone. We must accept a new mind teched by algorithm, and yet attempt to hold the simultaneous belief that we aren’t entirely doomed to consume in such staggered, unkempt, inattentive-laden ways. Needless to say, the amount of opinions and essays presented on Notes is neither mentally feasible nor intellectually stimulating. I often recede into a slew of quarter read essays about vacillating, though simulative, topics, until I must click out. It seems one can resist an algorithm only consciously and with great effort.

I began writing so as not to grow inert. I have always been disturbed by deep thought and detrimental rumination; a mind so riddled with anxiety lies in a spherical state of inertia. Writing is how my thoughts become active in the wider world. I was always partial to it, even when young, and better at it than any other subject. Somewhere around middle school I (sadly) ceased reading books for pleasure and became fixated on journalism, which I studied for the first two years of college only to switch majors mid cycle and end up with an Art History degree—a real regret. But I loved art, too. And film, music, video, fashion. I had this youthful, flimsy idea of what it meant to be artistic, and it largely didn’t include language at the time. (More on this in a next essay…)

But the freedom on Substack to write, about whatever! And to still write onself into a rut. The critical essay is what I mostly consume ad nauseum, trailed by their concomitant discourses on Notes. I find writing critical essays fulfilling but also arduously slow burning and thus, often, depleting; I can’t dwell in the ruminating mind for too long. The more visual, aesthetic, intuitive parts of my brain need to express, and read, their language equivalents, which I perceive to be more creative forms like poetry but also short stories or even streams of consciousness. (I find Matthew Gasda’s Writer’s Diary to be the best of this form; his series has served as inspiration for me as I think about future writing in this space.)

As Glenn O’Brien wrote in 2014, in his review of an art show:

The poet Max Blagg and I wandered the aisles hoping outrage and epiphany. We found lots of irony instead. The art world is in a most ironical mood, it seems. We discovered little but gestural humor at high prices. Tongues were impacted in cheek. Starved for the shock of the new, we were offered instead the persistence of the same old same old.

Starved for the shock of the new. The title of my Substack, In Praise of Thought—which is also the title of my book of poems—meant to describe a pleasure in knowledge, but also a delight in the possibility of using knowledge for renewed means. Reading to connect but also create. Thinking in turns rational and spirited.

How can I make, and find, writing less algorithmic? To balance my writerly need to be seen and read with a more important need to create something interesting? To weigh the importance of formal study and mastery, of external critique (and the very real need for an editor) with the freedom that can arrive from creating from a more feeling part of the intellect? To balance my love for critical journalism with more aesthetic forms like poetry? This is a vow and a plea for writing on here— my own, especially — to be more generative, more spirited, more interesting, more creative. Also, to heed an algorithm less, take pleasure in the process more.

As Glenn O’Brien wrote…tweeted, actually…(again, gleaned from Intelligence for Dummies, which is obviously an instructional text for me), “I’m not content with content. I want to be a contempt provider.” O’Brien was a funny, witty, and even ironic kind of writer, but he never wrote with cynicism. I take his tweet as a prodding of our online proclivity to rest, and recreate, in this mimetic state of inertia.

In this vein, and all that writing to say, I will begin a new series on this Substack—a less edited, less formal, more creative, and more regular (to be published weekly) writing. Separate from my more formal, edited and finished poems, these will be poetic experiments in first draft form. I will continue my critical and philosophical essays as well, publishing them as they are completed; which means they take time, and time I will take.

The first of this new series will arrive this Friday.