To pick one line from a haiku when there are only three feels futile. A haiku functions as one piece, a unit of syllable and deceptive brevity, a cover for writing of the utmost discernment. A haiku relies on rhythm, thoughtful language, and the writer’s concerted presence. Each line is brimming with consciousness in both word limitation and ethos. Haiku, in its purest form, is an objective observation, one that traditionally seeks to illuminate the natural world. By following haiku “rule,” the poet remains a neutral observer, foregoing any projection or interpretation of its subject. It is meant to be a study in pure presence, an acceptance and exaltation of what is.

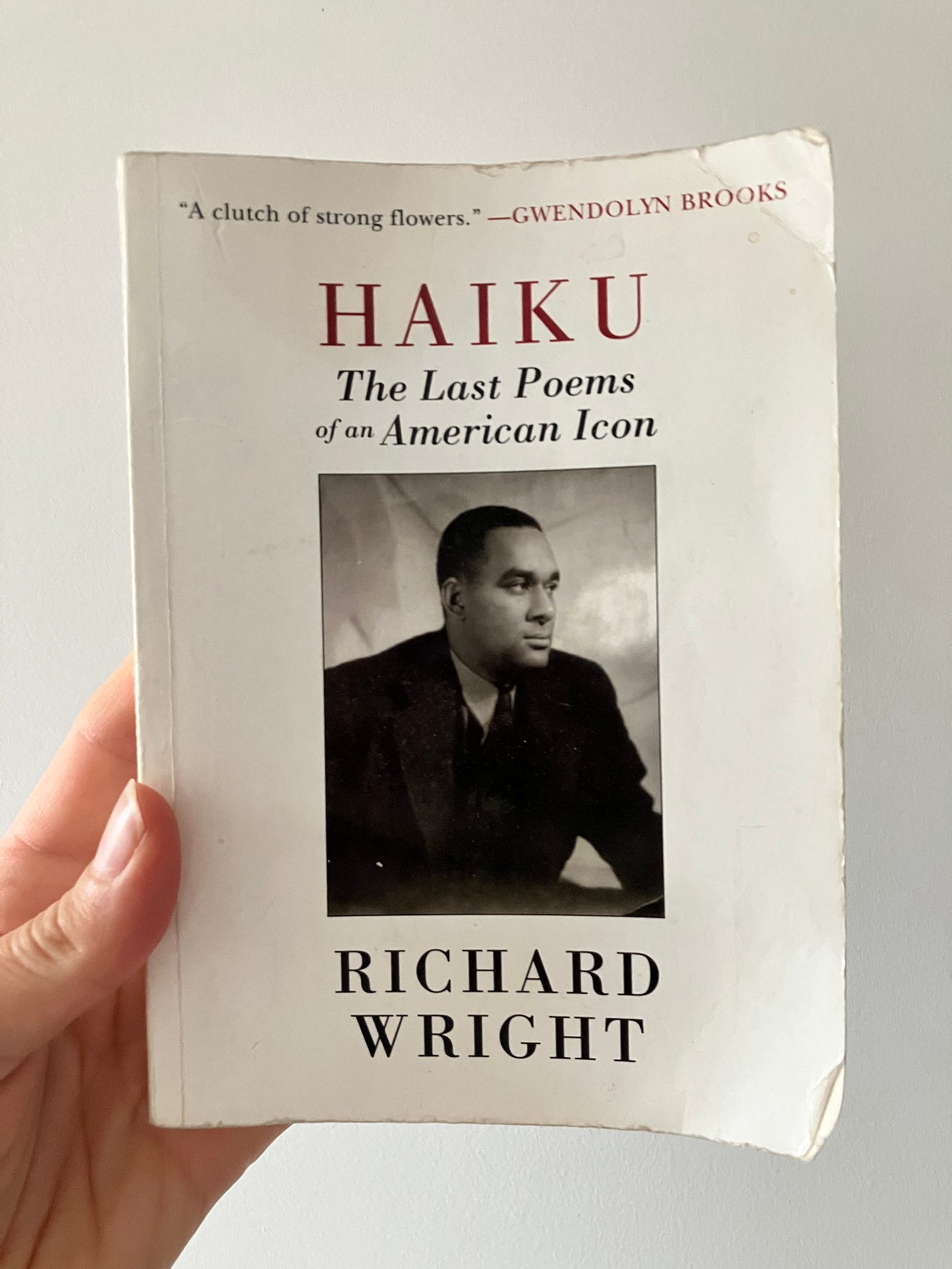

Before wandering into a bookstore in San Francisco and randomly stumbling upon a book of haiku by American-born writer Richard Wright, I knew as much about this poetic form as the rest of the lay world. I recognized a haiku only vaguely as a short poem. I knew of its structure: 5 syllable/7 syllable/5 syllable. But it was really Wright’s name that stuck out from the shelf, having previously read Native Son, his most influential novel, an early and unflinching work on race published in 1940. I didn’t know Wright as a poet and was intrigued to find he had written thousands of haiku, assembled his favorite into the collection I was now leafing through. Since I tend to write prose, I have grown in deep curiosity for form, yearning for structure as a means to greater creative freedom. (By comparison, boundlessness can feel quite anxiety-inducing—something one might apply to life and relationships as well).

I was enamored by first poem, not only because of the surprising expansiveness, but because it was language like a deep inhale; a poem of so few words, occupying such little space, yet so broad in melody and perception. (Is this what brevity can do?) Wright wrote these haiku while living in the South of France, sick and eyeing death. One could sense he had accrued a certain Zen-like wisdom that mortality can bring. His daughter wrote of an obsessive writing practice, watching her father scribble haiku in notebooks and on the backs of napkins in cafes, stringing them around his studio by clothes pins. As I flipped through the collection, I recognized these poems as alms to a world that had served as backdrop, for the society he spent a lifetime analyzing. Indeed, his novels were of canonical importance to American literature, have inspired the works of our most celebrated writers, James Baldwin included. In the final moments of his life, an ailing expat in France, he attained a certain distance from the oppression of our American racial constructs, which had rightfully guided his work. In France, he earned space to be still, to observe without scrutiny.

There are themes woven throughout the collection: one being nature, of course, but another being Wright himself, his particular eye. No matter how neutral a poet is wont to be, individual discernment bleeds through, the particularities of that which they seek to exalt. We are the lucky recipients of this attention, are called to attention ourselves. Some of the haiku break their “rule” of nature, illuminating instead a feeling, friend, or more strikingly, himself; these rogue ones happen to be my favorite.

Many of them favor flowers—magnolias in particular, which must have been a beloved sight given his childhood spent in the American south. Each poem is numbered without title. I chose to highlight haiku #383 because it demonstrates keenly how nature can be summoned in brief and vivid language.

Softer than sound,

The moon-struck magnolias

On a still hot night.

Softer than sound. A night not void of sound but full of something softer: an ambient lull of nature, a particular white noise. The moon-struck magnolias. How the moon doesn’t so much illuminate as it casts its subject in striking play of light and shadow. On a still hot night. One can conjure such a summer’s eve, the kind of heat that slackens time to hover. Wright memorializes this small slice of time, an innocuous, fleeting scene that readers will continuously reconstruct throughout time, as I am doing now, 70 or so years on. The most poignant thing is that this moment—a flower blooming, a warm evening—does not need to exist in the context of any story—or even Wright’s own life—to have meaning. It is meaningful in and of itself, in its sheer existence. This ode to nature does not instruct. It only helps to inspire a recognition within us to look outside of ourselves, to the things we have tended, with time, to notice less, to express in language even less. We are, of course, more inclined to record such moments through a phone’s lens than by poem.

Haiku is an ancient form, stricter in awareness than a photograph could ever be. It requires no apparatus between one’s sight and the object of attention; it requires only sentience. It perhaps remains more relevant, then, to a modern disposition. In our increasingly narcissistic and mindless world, haiku asks us to be present, to look, which might act as a remedy for modern malaise.

Perhaps death remains the only real truth that can really snap us into life—just as death, looming, led Wright to haiku. But haiku itself can teach us a necessary lesson too: let go of oneself—if for a moment!—and behold. Watch as a seemingly inconsequential tree or budding flower or well-worn sunset can hold more value than any limited human analysis might provide. Just watch the world exist.

Wright laid it out in the very first poem of the collection with startling clarity:

I am nobody:

A red sinking autumn sun

Took my name away.